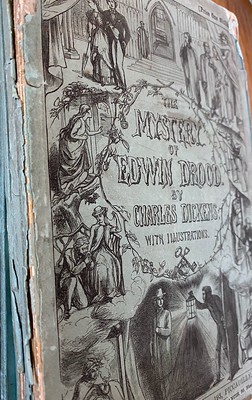

This should have been posted on the 8th, but I forgot to crosspost from Circumlocuted. Sorry. The six serial parts that make up

The six serial parts that make up The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Mrs Tope's care has spread a very neat, clean breakfast ready for her lodger. Before sitting down to it, he opens his corner-cupboard door; takes his bit of chalk from its shelf; adds one thick line to the score, extending from the top of the cupboard door to the bottom; and then falls to with an appetite.

When

Charles Dickens finished the penultimate chapter of the sixth instalment of

Edwin Drood, on this day 150 years ago, those were the final words he would ever write.

1 Later that evening he had a stroke, and he died the following day without regaining consciousness. While Dickens the man got up from his desk, dined, complained of a toothache and asked for the window to be closed before dying, Dickens as author dies with the final words of

Edwin Drood.

2 His final novel is indissolubly linked with its author's death, not least because the premature end to the life is the cause of the premature end to the text. Sometimes, there is speculation that it was the other way around: that the novel killed its author. I have written about the

narrative significance of Dickens' death elsewhere.

The propinquity of the last words of the last work and the death lent them some of the sanctity of the grave. Fans and opportunists (or opportunistic fans) who attempted to complete the novel were derided as a

ghoulish horde of hacks anxious to filch a portion, however, small, of his overwhelming popularity. (Matchett 296-7)

Starting from parody, through imitation, via spiritualist mediation, to inspiration and a musical intervention, attempts to provide the end to

Edwin Drood have faced opposition from those who wanted to safeguard the name of Dickens from intrusions and blots. The self-appointed 'greatest fans' (though they would probably choose the word 'enthusiast', or just plain 'Dickensian' -- and yes, I

am looking at you, J. Cuming Walters) were both deeply fascinated by the mystery and concerned that Dickens' reputation should not be compromised by taint to this final work. Which, 150 years after the man's death, with the newspapers full of the latest gossip about the man, article after article and book after book on the subject, may seem odd. But around the turn of the last century, Dickens' position was somewhat less secure, being rather too popular, rather too funny, and rather too political, all in all for certain arbiters of taste. His fans' paranoia was therefore perhaps excusable. A line was drawn between the good fan (the enthusiast) and the bad (the money-grabbing, often female or (the horror!) American, presumptuous enough to place themselves in Dickens' stead). The good could still play with the plot: J. W. T. Ley, in 1908 wrote that

there arose another class altogether -- a succession of people who produced genuine 'loving studies' propounding theories as to how Dickens would have developed the story had he lived. For the most part, these 'Droodists' (the latest name for them, which, to my astonishment, has not brought forth one word of protest. Mr. Cuming Walters must have suffered much for his temerity in entering the field, but I certainly thought this would be the last straw. Perhaps it was!) -- for the most part they have treated their subject -- shall I say reverently? -- that is, their inquiries have been generally marked by genuine affection (Ley 267)

And so, the text continued, slowly at first, and after a while faster and faster, spiralling, multiplying, spinning and quarrelling, to the delight of some and the dismay of many (because as Droodians divided themselves into good and bad, they were as a whole often seen as rather suspect in their preoccupation with plot rather than the delightful humour or characters that others saw as the truly Dickensian). The unfinished novel has been at the heart of an extraordinary volume of textual production: speculations build on and react to each other; completions write out possible endings; interventions investigate characters or scenes from other perspectives (sometimes in poetry); and scholars attempt to deal with this text which is unfinished, and yet steadily growing (sometimes by joining in, sometimes by picking one sexy theory and sticking with it; and sometimes by picking the least sexy theory, because science cannot with the frivolity etc).

Edwin Drood is dead. And alive. John Jasper murdered his nephew because of his desire for Rosa Bud (or her inheritance). And because he has a secret life as a Thug devotee of the goddess Kali. And he failed to murder his nephew because his opium use made him take a funny turn at the crucial moment. And he is wholly innocent of these slanderous accusations, only guilty of failing to protect his nephew (who is actually his younger brother) from an Egyptian blood feud. The true murderer is Grewgious, is Sapsea, is Neville hypnotised by Jasper, or Neville urged on by his sister. Datchery is Drood, is Helena Landless, is Bazzard, is Tartar (who is Drood), is Grewgious, is the uncle of the real Datchery, is Miss Twinkleton. Or just Datchery. And Datchery is the real John Jasper (who is presumed murdered by the impostor presenting himself as John Jasper in the story), and the real father of Neville and Helena. What is more, the impostor John Jasper has murdered Edwin Drood because he believes him to be the reincarnation of his first murder victim, the real John Jasper. And Datchery is Charles Dickens. The Opium Woman is Jasper’s mother; she is his former lover, or the mother of a girl he has wronged; she is Rosa’s grandmother, Jasper’s sister, and Edwin Drood’s step-mother. Or something else entirely. Edwin Drood is a story about the criminal mind, the orient, mesmerism, telepathy, the corruption of the Anglican church; it culminates Dickens and prefigures Christie, and Dostoevsky, and Stevenson. Dickens does not escape this spiralling text: when he is not Datchery, he is the fallen author killed by his own creation, the triumphant genius anticipating

Crime and Punishment,

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

The cover of the monthly wrapper.

The cover of the monthly wrapper.Readers have found inspiration in the text, his manuscript, the proofs, the illustrations of the monthly wrapper, in Dickens' life, his other books, his letters, statements from his family, friends, his illustrators, books he had read, and books he did not live to see. Attempts to nail down the text, once and for all, like

The Dickens Fellowship Trial of 1914 (and the many that followed), keep opening it up.

If you want a friendly introduction to the mystery, I can recommend Pete Orford's

Drood Inquiry, which provides a clear and comprehensive overview of some of the questions that have preoccupied Droodians through the ages (and if you are more analogue than digital, he has also written an excellent and accessible book on the subject!). Get creative. Have fun. I don't think anyone has written a theory based on

the ads that surrounded the text at the time, for example. Take comfort in the fact that others have gotten carried away before you, like

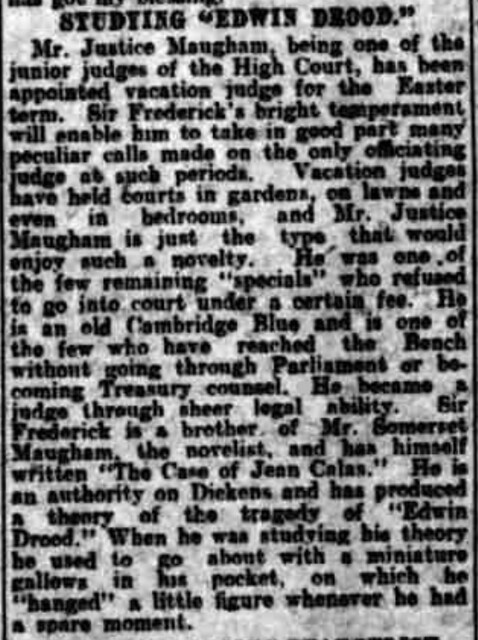

Justice Maugham, who while studying the problem would carry around a tiny gallows to hang the culprit.

From the

From the Belfast Telegraph 29 March 1929.

Enjoy! (And hopefully, this time or so next year, I will have another book for you to read on the subject.)

1 If you are interested to see the final manuscript page, you can find it

here.

↩2 The accounts of Dickens’ final words vary. Forster reports that ‘”on the ground” were the last words he spoke’ (Forster 1874:501). Several newspapers reported that he had said he had a toothache and asked for a window to be shut (e.g. ‘Last Hours of Mr. Charles Dickens’). Meanwhile, the

Times, perhaps finding all these too prosaic for a great author, reported that Dickens ‘was with his last breath instructing his children in the secret of his success … --“Be natural my children, for the writer that is natural has fulfilled all the rules of Art”’ (‘The Late Mr Charles Dickens’).

↩'The Late Mr Charles Dickens'.

Times (June 11, 1870): 9.

'Boxer Who is Managed by his Wife; Duke's Trip to Japan; Ramsay, Golf Enthusiast; Judge Who is a Novelist'.

Belfast Telegraph. (29 March 1929):7.

Dickens, Charles.

Edwin Drood. Chapman and Hall, 1870.

Ley, J. W. T.. 'The National Dickens Library'.

Dickensian 4 (October 1908): 266-9.

Matchett, Willoughby. “A Great Mystery Solved.”

Dickensian 9 (November 1913): 296–97.

The Drood Inquiry.